New React developers are often confused when they encounter

two different styles for declaring React components.

The React ecosystem is currently split between the

React.createClass component declaration:

const MyComponent = React.createClass({

render() {

return <p>I am a component!</p>;

}

});

And the ES6 class component declaration:

class MyComponent extends React.Component {

render() {

return <p>I am a component, too!</p>;

}

}

Have you been wondering

what the difference is between

React.createClass and ES6 class

components?

And why they both exist? And which you should use? Read on ...

First, a little history...

As a prototypical language, JavaScript didn't have classes for much of its existence. ES6, the latest version of JavaScript finalized in June 2015, introduced classes as "syntactic sugar." From MDN:

The class syntax is not introducing a new object-oriented inheritance model to JavaScript. JavaScript classes provide a much simpler and clearer syntax to create objects and deal with inheritance.

Because JavaScript didn't have classes, React included

its own class system. React.createClass allows

you to generate component "classes." Under the hood,

your component class is using a bespoke class system

implemented by React.

With ES6, React allows you to implement component classes that

use ES6 JavaScript classes. The end result is the same -- you

have a component class. But the style is different. And one is

using a "custom" JavaScript class system

(createClass) while the other is using a

"native" JavaScript class system.

In 2015, when we broke ground for

our book, it

felt like the community was still largely mixed. Key figures

from Facebook were stating that the

React.createClass style was just fine. We felt it

was easier to understand given that developers were still

adopting ES6.

Since then, the community has been shifting towards ES6 class

components. This is for good reason. React used

createClass because JavaScript didn't have a

built-in class system. But ES6 has enjoyed swift adoption. And

with ES6, instead of reinventing the wheel React can use a

plain ES6 JavaScript class. This is more idiomatic and less

opaque than the custom class generated by

createClass.

So, responding to the momentum, we decided to move over to ES6 class components in the book.

For the developer, the differences between components created

with ES6 classes and createClass are fortunately

minimal. If you've learned how to write React components

with createClass, should you ever want to use ES6

classes you'll find the transition easy.

Creating components with createClass()

To compare the two component styles, let's implement a checkbox as a React component.

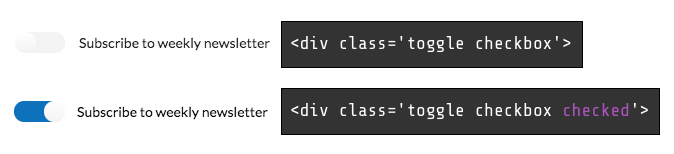

In the CSS framework we're using, we can toggle whether or not a checkbox is checked by changing the class on a div:

When using React's createClass() method, we

pass in an object as an argument. So we can write a component

using createClass that looks like this:

const ToggleCheckbox = React.createClass({

getInitialState() {

return {

checked: false,

};

},

toggleChecked() {

this.setState((prevState) => (

{ checked: !prevState.checked }

));

},

render() {

const className = this.state.checked ?

'toggle checkbox checked' : 'toggle checkbox';

return (

<div className={className}>

<input

type='checkbox'

name='public'

onClick={this.toggleChecked}

>

<label>Subscribe to weekly newsletter</label>

</div>

);

}

});

Using an ES6 class to write the same component is a little

different. Instead of using a method from the

react library, we extend an ES6 class

that the library defines, Component.

Let's write a first draft of this ES6 class component. We

won't define toggleChecked just yet:

class ToggleCheckbox extends React.Component {

constructor(props, context) {

super(props, context);

this.state = {

checked: false

};

}

render() {

// ... same as component above

}

}

constructor() is a special function in a

JavaScript class. JavaScript invokes

constructor() whenever an object is created via a

class. If you've never worked with an object-oriented

language before, it's sufficient to know that React

invokes constructor() first thing when

initializing our component. React invokes

constructor() with the component's

props and context.

Whereas before we used the special React API method

getInitialState() to setup our state, with ES6

classes we can set this.state directly here in

the constructor. Note that this is the

only time we'll ever use

this.state = X in the lifetime of our component.

Beyond initializing the state we must call

this.setState() to modify the state.

We invoke super() at the top of

constructor(). This invokes the

constructor() function defined by

React.Component which executes some necessary

setup code for our component.

It's important to call super() whenever

we define a constructor() function.

Furthermore, it's good practice to call it on the first

line.

Because our component doesn't use props or

context, it's OK to not pass those along:

class ToggleCheckbox extends React.Component {

constructor() {

super();

// ...

}

}

Now let's add toggleChecked. The

implementation of the method is the same as before:

class ToggleCheckbox extends React.Component {

// ...

toggleChecked() {

this.setState(prevState => ({ checked: !prevState.checked }));

}

// ...

}

Except, this wouldn't work as expected. Here's the

odd part: Inside both render() and

constructor(), we've witnessed that

this is always bound to the component. But inside

our custom component method toggleChecked(),

this is actually null.

In JavaScript, the special this variable has a

different binding depending on the context.

For instance, inside render() we say that

this is "bound" to the component. Put

another way, this "references" the

component.

Understanding the binding of this is one of the

trickiest parts of learning JavaScript programming. Given

this, it's fine for a beginner React programmer to not

understand all the nuances at first.

In short, we want this inside

toggleChecked() to reference the component, just

like it does inside render(). But why does

this inside render() and

constructor() reference the component while

this inside toggleChecked() does

not?

For the functions that are part of the standard React

component API like render(),

React binds this to the component for

us.

Indeed, this is why we had no issues when using

createClass to define our component. When using

createClass, React binds every method to

the component. That's one of the biggest differences

between createClass components and ES6 class

components:

Any time we define our own custom component methods for an

ES6 class component, we have to manually bind

this to the component ourselves.

There's a few patterns that we can use to do so. One

popular approach is binding the method to the component in the

constructor(), like this:

class ToggleCheckbox extends React.Component {

constructor(props, context) {

super(props, context);

this.state = {

checked: false

};

// We bind it here:

this.toggleChecked = this.toggleChecked.bind(this);

}

toggleChecked() {

// ...

}

render() {

// ...

}

}

Function's bind() method allows you to

specify what the this variable inside a function

body should be set to. What we're doing here is a common

JavaScript pattern. We're redefining the

component method toggleChecked(), setting it to

the same function but bound to this (the

component). Now, whenever

toggleChecked() executes, this will

reference the component as opposed to null.

At this point, both of our components will behave exactly the same. While the implementation details under the hood are different, on the surface the variance is relatively minimal.

The "binding" quirk for ES6 class components is a little perplexing. You'd be right to ask: React aside, why doesn't

thisinside an ES6 class method reference the instantiated object?We think this answer on Reddit sums it up nicely:

Because ES6 classes are mostly syntactic sugar for the existing Javascript prototype inheritance behavior, per this example:

function MyFunction() { this.a = 42; } MyFunction.prototype.someMethod = function() { console.log("A: ", this.a); }; var theInstance = new MyFunction(); theInstance.someMethod(); // "42" var functionByItself = theInstance.someMethod; functionByItself(); // undefinedIn the same way, a function defined as part of a class doesn't get

thisauto-bound by default - it's based on whether you're calling it with the dot syntax, or passing around a standalone reference.

An alternative ES6 class component style using property intializers

Because of this, ES6 class components come with this bit of extra ceremony. In our own projects, we use an experimental JavaScript feature called property initializers. While not yet ratified for JavaScript adoption, the proposed syntax is compelling. It provides a terser syntax for both initializing state and ensuring custom component methods are bound to the component. To give you an idea of why this experimental feature is popular among React developers, here's what our component would look like re-written using property initializers:

class ToggleCheckbox extends React.Component {

// state initialized outside constructor

state = {

checked: false

};

// Using an *arrow* function ensures `this` bound to component

toggleChecked = () => {

this.setState(prevState => ({ checked: !prevState.checked }));

};

render() {

// ...

}

}

We'll discuss property initializers -- and how to use them in your projects -- in further detail in a subsequent blog post.

EDIT: That blog post is live!

Which should you use?

Ultimately, which component declaration method you use is up

to you and your team. While the community is moving towards

ES6 class components, if you're already using

createClass widely there's no need nor rush

to upgrade. And should you decide to change to ES6 class

components in the future, there are automated tools to help

you do this easily like

react-codemod. (If there's enough demand, we'll write a blog

post about this process, too)

If you'd like to read more about binding and ES6 classes, check out these two links:

- Why aren't methods of an object created with class bound to it in ES6? (Stack Overflow)

- Binding Methods to Class Instance Objects (Pony Foo)

Because you found this post helpful, you'll love our book — it's packed with over 800 pages of content and over a dozen projects, including chapters on React fundamentals, Redux, Relay, GraphQL, and more.